"...pulsing, deep-pocket grooves..." Gregory Isola-Bass Player Magazine

"Even the simple things must have character and depth and feeling." --Harlan Terson

SWEET HOME

CHICAGO

Four Blues Bass Masters

"It’s like picking a route. You have to be at a certain place at a certain time,

but you can find an interesting way to get there."

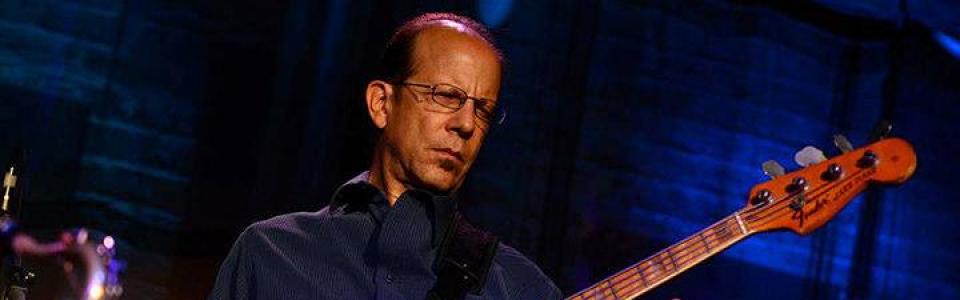

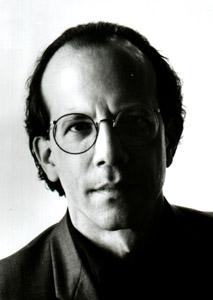

That’s how Harlan Terson sums up blues bass playing, something he’s done professionally for more than two decades. The 40-year-old is just one of Chicago’s great blues bassists. They’re a diverse group: young and old, black and white, funky and traditional. To get a feeling for what it takes to be a blues professional, we checked in with Terson and three other outstanding players: Greg Rzab, Noel Neal, and Johnny B. Gayden. Although they’ve all played "Sweet Home Chicago" dozens of times, each one always finds a way to make it sound fresh. Here’s how they do it.

Harlan Terson

While Noel Neal envisions himself leading a band, others are content to remain in the background. "You have your show-off instruments and your rhythm instruments," says Harlan Terson, a 25-year veteran who’s played with Lonnie Brooks, Bo Diddley, Eddie Shaw, Steve Freund, and others. In many ways, Terson and Neal represent the opposite ends of the blues bass spectrum. "I play in the more traditional style, and I don’t get bored with it," says Harlan. "I see bass as a disciplined instrument. I’m a sideman, and I do my best to make the guy up front look and sound good. That’s even more important when you’re an independent contractor, because you have to make the bandleaders recognize you. Even the most simple thing you play has to have character and depth and feeling—it can’t just lie there. If your lines move the music forward, then the whole band sounds good."

Terson grew up in Chicago, absorbing the blues he heard all around him. His first instrument was guitar, but he switched to bass when he discovered there weren’t enough bassists to go around. "I listened to Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and blues-based bands like Cream and early Jethro Tull. I thought, ‘Rock is just blues played really loud." I also heard a lot of Motown and played in a soul band. Learning the lines of bassists like James Jamerson, Carol Kaye, Jerry Jemmott, and Duck Dunn was really inspiring."

After playing local gigs as a teen-ager, Terson earned a degree in music at the University of Illinois in Chicago—"It was just a technical explanation of everything I’d already been doing"—before launching his career as a full-time pro.

His first steady gig was in a band led by guitarist Sonny Wimberly, a former sideman with Muddy Waters. Harlan went on to play with ex-Canned Heat guitarist Mark Skyer, and then joined the Lonnie Brooks band in 1976, where he stayed for six years. He made his best-known recording with Brooks, a live version of "Sweet Home Chicago" recorded at Chicagofest ’80. It was included on the Grammy-nominated Alligator album Blues Deluxe and still gets played on the radio (at least in the Windy City).

These days, Terson can be heard regularly with the Frank Pellegrino Band and a cooperative group known as the Fabulous Fish Heads. He also freelances extensively and is often called in at the last minute—or ten minutes later—to play with an unfamiliar band. "If you’re going to do that, you have to be completely professional. You’ve got to have reliable transportation, show up on time, have a backup system. And when you’re there, you have to really listen."

"The blues is the soundtrack of my life," Terson says. "It just gets in your blood. It’s not even a conscious choice; it’s like you’re almost chained to it, even though you might be more successful playing something else. The bands change like the weather, and it can be discouraging. Thankfully, I’ve been able to make a living playing music for a long time—although there’s more to it than money. There are a lot of better-paying gigs, but not many offer the same satisfaction. The blues may seem restricting, but there’s always an interesting way to play it. You keep growing and generating fresh ideas, although I don’t get carried away—a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing on a rhythm instrument."

From Bass Player, July/Aug 1991

Copyright Miller Freeman, Inc. used by permission.

SOLID

A Conversation with Harlan Terson

A Conversation with Harlan Terson

by Cathi Norton

I was sitting in the middle of the crowded club; grateful we'd scored some seats because the place was packed. A few frat boys were smokin' big stogies and grossing out their dates right in front of us, but we politely ignored them, bigger things on our minds. The band had been oiling up the machinery for about fifteen minutes when Otis Rush came out. He strapped on that sweet looking, red Gibson 335 and the minute his fingers hit the strings…heaven. His backup band that night was a little rough, but we hardly noticed because Otis, all alone in a huge crowd, commanded our attention. He didn't even have to speak; the romance between his fingers and his guitar said it all.

In the middle of this double-Dutch treat for the ears, I noticed small cues between him and band members that said things weren't going right. He gave quick instructions before a couple of the numbers and even played the bass line a few times to give the bass player hints, but something was jamming up the works. The band got more ragged as Otis's lips got thin and he struggled to overcome his irritation. (The runaway downward train -- I know it well!) Though the crowd didn't seem to notice, I got antsy, as did my musician companions. The band's sound was going downhill fast. Even the frat boys were starting to notice when I saw Otis wave a man toward the stage and announced a guest would sit in. A slight guy quietly took the stage and threw the bass strap over his shoulder. He didn't look too flash--faded right into the backup band scenery. But when Otis counted off the tune, the whole band seemed to click into place. The Volkswagen had turned into a Cadillac. I don't think I could have commissioned a better example of what a difference a good rhythm section can make. I had a fabulous evening, well aware that I was listening to something special and rare. I doubt there's anybody better than Otis. I couldn't get that bass player out of my mind.

I asked for his name and promptly forgot it in the rush of activities that weekend. Time moved on and then another night, another month, another state, another club later, there he was again, quietly setting up his gear to back up Alex Schultz and Tad Robinson. I've got a secret weak spot for backup musicians who work hard, play great, and remain unnoticed. Maybe like all the famous musicians I've admired were once. And of course, like so many of us who never "make it" but hold the basic fabric of music together. I waited no longer.

His name is Harlan Terson, and he is just what he seemed: a solid player who makes his living as a bass-man-at-large in the highly competitive Chicago blues scene. Born there in 1951, Terson got a guitar in 1963 and began learning folk music from records and chord books when the Beatles and Stones brought the blues to him. "I was this long-haired teenager listening to 'Cream' do 'Howlin' Wolf,' and I didn't even know what's in my own back yard!" But Chicago favorites Paul Butterfield, Mike Bloomfield, the Siegal-Schwall Band and others made their presence known and before long Terson was making trips to "Alice's Revisited" (now a dance club called "950") to see Muddy Waters. "When I realized where all this music was coming from, that's kind of when the jig was up," Harlan laughs.

Terson played guitar for awhile in bands, but soon realized there was a greater need for bass players. Once he started, he realized he had a real penchant for it. He earned a degree in music at the University of Illinois--Chicago and went into music full time. A friendship with former Muddy Waters' sideman Sonny Wimberly led to steady club work. From the first Terson was skilled and dependable, valued qualities in a player. He worked with Mark Skyer (Canned Heat), did six years with Lonnie Brooks' band, and freelanced everywhere--still does. His reputation as a studio session man is equally broad after recording with Tad Robinson, Lurrie Bell, Dave Specter, Deitra Farr, Eddie Shaw, Lonnie Brooks (Brooks' album "Blues Deluxe" was nominated for a Grammy), Steve Freund, and many others. In traditional Chicago style, Terson lives from gig to gig, but his abilities keep him eating, and his love for the blues keeps him happy. Any full-time player knows it's a tough business that takes something special to sustain. Harlan's got it.

CATHI: So you really hit the steady giggin' in the early '70's?

HARLAN: I started with Sonny (Wimberly) in '75; went with Mark (Skyer) probably in '75, because I started playing with Lonnie (Brooks) in '76. It was a progression.

CATHI: What was the Chicago scene like then?

HARLAN: Well, I have a partner, Bob Levis (guitarist) who has played with me since high School. We still play together a lot. We're like a rhythm section that kept picking up front guys. Each band was a little bit higher of a level. Back then there was a small club scene that young bands did and then there was the blues scene that started to move up to the North side. Not really many whites went down to the south side back then. But up north the "Wise Fools" club was a place we could play. I played there with Lonnie.

CATHI: And you stayed with Lonnie for six years? Now his son Ronnie has his own thing too I see.

HARLAN: Yeah, six years, several records, some Europe. It was a nice band, really very family-like. When I was with Lonnie his sons Ronnie and Wayne were just little kids. Now Ronnie teases me every time he sees me because I used to kick him out of the basement. The kids would drive us nuts.

CATHI: (Laughter) What would they do?

HARLAN: Aw, they just wanted to come down there -- they loved music! You can see they're both successful musicians now. They just wanted to come down, bop around, and dig it.

CATHI: That band had to be a wealth of experience for you. What happened after it?

HARLAN: Well Ken Saydak, Steve Freund, and I put a band together. It was called the "Blueprints" and that lasted maybe a year or so.

CATHI: That was before Steve's gig with Sunnyland Slim?

HARLAN: Well, Steve held down that gig at B.L.U.E.S. -- and the Sunday Night Blues even before it was with Sunnyland. He was with Big Walter Horton and Floyd Jones -- he was there a long time!

CATHI: So then what (laughter)?

HARLAN: Well I played in various bands at the "Kingston Mines," and in a Motown Soul Band called "Rhythm City." And this is where it gets terrible Cathi, I started gigging around everywhere.

CATHI: Why is that terrible Harlan?

HARLAN: Well, it's not real inspiring.

CATHI: I don't know…speaking as a well-traveled musician I gotta say, sticking it out is pretty darned inspiring.

HARLAN: It takes a certain amount of guts just to stay in the business. I just wish I pursued a steady band--like Tad's (Robinson) for instance. But that is the exception these days.

CATHI: Let me ask about that. How do you maintain yourself?

HARLAN: I get on the phone and hustle (laughs). I try to maintain steady relationships with the bookers and I have to fight for my position. It's ironic. It's a stressful life because it's so uncertain, but it's easy (laughs). I mean, that's why I do it -- it's one of those paradoxes. I do this better than anything else. I could never see the point of having a 9-5. I always thought that would just break me.

CATHI: Well, your playing is really in the pocket, yet you don't do much grand-standing. What's your basic playing philosophy?

HARLAN: Well, playing gets in your blood. You've got to be reliable, show up, make the front people look good, get out there and really LISTEN.

CATHI: So do you want to travel?

HARLAN: I think I'd like to do more of that now. I need to find the balance between travel and paying the bills. I don't have an extravagant life, but I'm not mean with myself either (laughs). So I do whatever it is I need to do to maintain this not-extravagant-but-okay-to-myself-lifestyle. I have to get paid and sometimes sticking around here is the easiest way to do that. But then I have more visibility at festivals…so it's a balance.

CATHI: As a side-man can you get an agent to help you book or do you have to scuffle along on your own?

HARLAN: Scuffle! If there is a way an agent can help a side-man I haven't found it -- please let me know!

CATHI: (Laughs) If I do -- I'll be doing it! What about recording? You have a big discography.

HARLAN: About 20 records I guess.

CATHI: Do people call you in just for studio work or is there a rehearsal period?

HARLAN: If I'm lucky. Maybe we'll rehearse a bit; it depends on the situation.

CATHI: Say I wanted to hire you to do a record. What would be your general fee?

HARLAN: I would beg and plead with you to drag every dime out of your pocket I could.

CATHI: (Laughter) Okay.

HARLAN: And then we'd meet in the middle somewhere. Measuring what you're worth is a challenge for any artist, don't you think? Price often depends on whether you've got a demo situation going on or a full-blown record on a label.

CATHI: What's your local choice for studio drummer?

HARLAN: Well I work with Ken Smith -- Willie ("Big Eyes" ) Smith's son. He's an excellent young drummer. He's got the tradition and is a very nice young man.

CATHI: Tell me more about Lonnie (Brooks).

HARLAN: Okay, what do you want to know? Lonnie's like a father to me. I was in my mid-20s and still getting experience when I worked with him. I got recording and traveling experience in that band, so yeah, that's a big marker in my life--with Lonnie. Lots of seasoning and lessons.

CATHI: And you've worked with Lurrie Bell? He's got that see-saw rickety history like his dad (Carey Bell) in a way.

HARLAN: Yeah, I've been on the last three things he's done--the last one still in the can. He's an amazing talent. He's got some demons…it's (playing with Lurrie) like catching lightning in a bottle. But on his last album I got the opportunity to write some songs!

CATHI: Great! Do such things pay residuals?

HARLAN: I'll let you know (laughter).

CATHI: So how'd you hook up with Tad Robinson?

HARLAN: Through Steve Freund. Tad's a beautiful guy. That's one of my favorite situations. Great singer, very nice man, and the group he puts together is very enjoyable to work with. I don't work with them as often as I'd like, but I think we're going to do more work behind his new record. I've been working with Dave Spector a lot these last couple of years. He gives me not only work opportunity, but recording stuff.

CATHI: He's doing a lot of producing?

HARLAN: Some. He's done his own albums and Lurrie's. I hooked up with Tad through him and a lot of Delmark work has come to me through him.

CATHI: Deitra Farr too?

HARLAN: I've known her for a long time. We used to work at "Kingston Mines." Typically with recording there'll be one or two rehearsals -- both taped. Then we'll have some way to work with the material. But you can't just go in to record the blues. You got to make it a part of you first. To really play a song well you have to feel it; hear it in your head. It actually becomes a part of you. And then once in awhile you gotta tackle something different to keep proving something to yourself.

CATHI: How about the Chicago scene today?…or the blues in general? Any observations on that? Do you think it's all turning into rock?

HARLAN: Well I would say the scene now is more of a tourist thing than anything artistic, but it does give bluesmen work. Blues getting rock-y was just inevitable. We're no longer living in a world that's regional and isolated. There's too much media, too many people getting around, and that's how culture travels and changes. Blues is no longer something players pick up where they live. They hear many more influences and musicians everywhere.

CATHI: What's it like to work with Otis (Rush)?

HARLAN: It's a BIG DEAL! Because he's OTIS RUSH!! What are you gonna say? It's an honor for the guy to call you. I worked with him for a couple of years, though I've know him for about 20. I did a European tour with Otis. He's amazing.

CATHI: So now though you continue your side-man duties, you also have a band?

HARLAN: A collective of friends. We call ourselves the "Fabulous Fish Heads." I try to function in as many different situations as I can so that if one things goes down, others are still moving.

CATHI: What kind of gear do you use?

HARLAN: Several different things. I have a lot of Peavey stuff. I use a Mega Bass and an older Peavey head. I have a couple of older Peavey amps -- four different rigs depending on how much power I need. I'm pretty much into solid state amps. The bass I use now is actually a mongrel--a Fender Jazz Bass neck on a Precision Bass body. The vintage thing has gotten so out of hand and I once had a ''66 Jazz bass that got stolen.

CATHI: A heartbreak…man. Do you use the big 15" speakers?

HARLAN: One. I have different cabinets with 15's, but the one I use most now is a Bag End cabinet I got from the area -- very portable and small. I have to move this stuff you know -- I'm old (laughs).

CATHI: (Laughs.) Me too. So what would you tell someone who wanted to go into blues these days?

HARLAN: Maybe I would quote Bob Stoger (another GREAT bass-man-about-town in Chicago--cn). I was in Europe with Dave Spector and Bob was at the same festival. He's been very nice to me. I was sort of crying to him. "Bob, I'd really like to do more of this stuff. What should I do?" And he said, "Play your ass off! Make people sound good! Talk to people!"

CATHI: (Laughs) Good for him!

HARLAN: So I say, "Keep hanging around," I guess. Network; talk to people. And a little patience never hurts a human being in any endeavor. Nothing happens overnight. It's like you wake up one day and see what your life is, and it's not what you planned. I mean you can make action plans and that's good, but mainly you just gotta do what you gotta do for that day. That seems to work; doing the next right thing. Sometimes it's a spiritual struggle. Am I doing the right thing? But I really love this, and we don't know how long we have. Not to do what seems to be right for you to do is not right -- can't be good. I don't know how long I have here and I've been lucky. I admit sometimes it's worrisome, but I've been able to do it.

CATHI: So would you call yourself an optimist Harlan? (Laughter)

HARLAN: I usually tell people I decided I'd be an optimist, but then I figured it would never work.

This interview © 1999 Cathi Norton. Used by permission.All rights reserved.

HARLAN LEE TERSON

Posted by Michalis Limnios BLUES @ GREECE on June 29, 2012

Harlan, when was your first desire to become involved in the blues & who were your first idols?

I started playing in my first band in 1966, at the age of 15. My friend Bob Levis, with whom I played in many bands, including Lonnie Brooks And Otis Rush, was already in this band when I joined it. While we were not a blues band, a lot of the music that we were playing was blues based, such as the music coming out of England. So I was playing that 12 bar progression before I even realized what it was about. At some point I had the revelation of hearing Albert King’s recordings. I soon understood that the blues was at the bottom of everything that I was into. I also came to understand that much of it was from my own city. I began to listen to more recordings, and was fortunate to be able to see a lot of the artists live. I saw Muddy Waters many times, also Howling Wolf, Jimmy Rogers and Otis Rush. I went out of my way to see Albert King whenever he was in town. I became a little obsessed. I listened to his Born Under A Bad Sign album every day for quite a long time.

What was the first gig you ever went to & what were the first songs you learned?

I began playing jobs with my first band right away. These were not club jobs, but local teenage venues and parties. We were not playing blues. We did the songs of the day that were on the radio, British invasion, soul, etc. When I was older, I began frequenting the club scene. By then I already had a lot of experience in playing in bands, and had watched and played a good amount of blues. When I was just out of college, I began playing guitar in a band with Sonny Wimberly, who I had originally seen playing bass with Muddy Waters. Bob Levis was also in this band. By this time, I knew most of the blues standards. We played a lot of jobs on the South Side of Chicago, and that is where I began a long career of club work. We also had horns in that band, and in addition to blues, we played a variety of soul tunes, which has always been common practice in Chicago blues clubs.

In the next band I played in, I switched back to the bass. In those days, I was also able to sit in with some of the great bluesmen like Otis Rush, and gig on occasion with others, such as Jimmy Rogers. In 1976, I met Lonnie Brooks, and that was a most important event for me.

Which was the best moment of your career and which was the worst?

It’s really hard to pick any one moment. But I think the best times of my life were my days in the Lonnie Brooks Band. I got the opportunity to help a very talented musician start a new band, and a new phase in his career, which turned out very well for him. I played on my first recordings with Lonnie. Two of those recordings were nominated for the Grammy award. I also did my first European tours with that band. It was a band with a feeling of family, and while we had our problems like any family, we enjoyed travelling together, and creating something together. What we started can still be heard in Lonnie’s performance today. I’m very proud and grateful for that.

I also have some great memories of my European tours and two tours of Japan with Otis Rush. It’s the amazing audiences that make those things really memorable. When it’s happening, the energy that goes back and forth between audience and musicians is the greatest thing that I have ever felt.

Sometimes it’s easy. Sometimes it’s difficult. Some moments are incredible. Sometimes you are just making a living as best you can.

What characterize the sound of Harlan Lee Terson? How do you describe you philosophy about the blues music?

I see myself as a traditional player. I started playing in the 60’s and I think that is reflected in the way I sound. In addition to blues, I’m especially fond of Southern soul. I like rock and roll, country, British invasion, the great American songbook, lots of stuff. I’m not very much into blues rock or metal. And I’m not out to reinvent the blues. I’m not looking for the latest trend. I am searching for that hypnotic groove that drew me in in the first place, and get deeper into it. I want to feel good. I listen carefully, try to hear my place in the mix, and solidly support the sound and dynamics of the band. I want to hear what I am going to play come to me. I don’t plan what I’m going to play, or try to play things for the sake of calling attention to myself. I try to present myself well, be on time, and dress reasonably decent, but I’m not trying for some kind of a “blues" look. Playing the blues allows me to be myself, and that’s one of the things that drew me into it. It allows for individuality in a traditional structure. I think that’s great.

Do you have any amusing tales to tell of your gigs and recording with Lonnie Brooks?

We enjoyed performing together. My first gig with Lonnie was at the Show And Tell Lounge on the west side of Chicago. We played all kinds of bars and clubs, and the occasional road gig. We used to do four night jobs at a couple of Chicago clubs, the Wise Fools Pub and Biddy Mulligan’s. At Biddy Mulligan’s there was an island bar and a small space between the bar and the bandstand where the people would dance all night long.

When we recorded Voodoo Daddy, the first song on the Bayou Lightning album, at one point Lonnie was on the floor on his back and we were all standing around him playing and encouraging him. I remember rehearsing for another Alligator recording in Lonnie’s basement, and his kids running around down there. Now those two little boys are grown musicians out on their own.

With Lonnie, I got to help build a very good band, record really good tracks, and do some interesting travel.

What does the BLUES mean to you & what does Blues offered you?

I’ve been very lucky. Music has given me purpose, identity, a way to see the world, to connect with people, a roof over my head, food on the table, love, and friendship.

Blues is a musical form that is best learned by experiencing it. Even before I heard played by real blues artists, I had a feel for it, through the rock and roll I heard as a kid. Playing it for me has been very natural, just like breathing.

What do you learn about yourself from the blues music?

I hear well, and I have a great feel for time. I’m part of a big picture. I can cooperate with other musicians to create something bigger than myself. I get along well with most people. I have something to offer.

What experiences in your life make you a GOOD musician?

I’ve loved music for as long as I can remember. I can still hear in my head the 78’s that my older brother was listening to in the 50’s. In fact, I can remember just about everything I’ve ever heard. When I was 12, my older brother bought a guitar. My cousin taught me some chords and a few songs, and I could play right away. Going to music school helped me to put a lot of things together, particularly the ear training part. I’m not saying that a person has to do that to be a good musician. But for me, it helped me to a deeper understanding of what I was doing. Being a bassist puts me in the position of always having to listen to what is going on and be the glue that holds things together. I enjoy making that work. I love it when the whole mix sounds great. I get the chance to drum every so often, with students, or at a jam. I’m not real slick, but I still have a great sense of time.

Do you remember anything funny or interesting from Otis Rush?

Before every song, Otis would turn around and play a little bit of the bass line to let you know what was coming. I also recall that I had a habit of playing some things a little bit staccato, and he would sometimes turn around and admonish me to “sustain the bass.” I was determined after a while to not have him do this, and I focused on getting the sound he wanted.

We did a European tour where I spent many late hours just visiting and talking with Otis, just about music and family and various things. He enjoyed the company.

What are some of the most memorable gigs and jams you've had?

Wow! There is so much that has happened over 35 or 40 years! My first European show was a TV show taped at a club in Hamburg, Germany with Lonnie Brooks. We also played at the Blues Estafette in Holland in 1981, along with Jimmy Rogers and Walter Horton. That was Walter’s last major festival before he passed away. My last tour with Lonnie was the Chicago Blues Giants European tour in 1982, with Eddie Shaw, Lefty Dizz, Ken Saydak, and Melvin Taylor. Some of the people who popped up on stages with Lonnie from time to time included James Brown and Johnny Winter. I have to say that I also loved playing locally in Chicago with that band, even little club gigs. There used to be lines of people all the way out the door at the Wise Fools Pup in the mid to late 70’s.

With Otis Rush, I would have to say that the Japan shows were the most memorable. He has a very devoted following there.

I played at the Lucerne Blues Festival twice with Dave Specter. That is a very hospitable festival and a very nice city to visit.

Of course, I’ve had the opportunity to do the Chicago Blues Festival a number of times with various artists. My last performance with Otis Rush was on that stage.

I’ve also played at the Trinidaddio Festival many times, a nice, friendly festival in Trinidad, Colorado. It’s always nice to go somewhere where the local people know you and welcome you back.

So many years, so many gigs! It’s been a great ride.

Are there any memories from Kingston Mines, which you’d like to share with us?

Ah, the Mines. I remember hanging out there in the original location (before the roof caved in), and playing there occasionally. I started working there (in the present location) quite a bit in the 80’s, with a lot of different people. At one point I must have been there five nights a week. Back then, the scene was very casual, and before the place expanded, we would park in the back and hang out a lot. You wouldn’t recognize the original layout. The place being open later than most, people would end up there every night. A lot of celebrities would come through, from Bruce Willis with an entourage like the secret service to Mick Jagger (with a very large bodyguard). I made a lot of friends there, and I am the godfather of M.C. Frank Pellegrino’s son Sam.

Do you have any amusing tales to tell from your meet with all those great musicians: Bo Diddley, Albert Collins, Sunnyland Slim, Eddy Clearwater, Jimmy Rogers, Eddie Shaw, Big Mama Thornton and many more?

I remember very well the big smile and laughter of Johnny Littlejohn. He was a mechanic. He once picked me up for a job in Atlanta, Georgia. On the way, he stopped at an auto parts store and picked up a part that he knew he would need on the road. He did that repair in Atlanta. On the way home the van had a problem He reached under the seat, pulled out a fuel pump, put it in, and we were on our way home. He was also a lot of fun to play with, and a very nice guy. I played on his last recording.

The Lonnie Brooks band backed up Albert Collins the first time Bruce Igluaer of Alligator Records brought him to town. We did the same with Big Mama Thornton.

Jimmy Rogers, and Eddie Shaw, both really nice guys. My one gig with Bo Diddley, very easy and fun. Steve Freund and Sam Lay were the other guys on that gig. Everyone loved Sunnyland Slim. Steve came all the way to Chicago from Brooklyn to play with Sunnyland Slim. Steve moved on to the west coast. I always found him to be an intense, passionate guitarist.

I’m lucky to have lived at a time when it was possible to play with all those legends.

As to some of these stories, they are better told in private!

From whom have you have learned the most secrets about blues music?

I learned from just listening and watching. I was fortunate to be around while many of the original artists were still here. And of course, there are the recordings. You learn it, you play it, and you respect the music and surrender to it. And if you can find your sound without trying to impose yourself on the music and make it all about you, then you’ve done well.

Some music styles can be fads but the blues is always with us. Why do think that is? Give one wish for the BLUES

These days, traditional blues has largely been lost to rock elements, particularly over the top guitar histrionics. I hope that there will always be at least a few people who are interested in finding out where this music comes from, who can stop and listen, and take care of it. There have always been strong personalities, and I understand that this is “show business”, but I think that the music has to be the most important thing. It is a strong music, and it can take a lot of abuse (and it has), but it should be respected and nurtured. And it needs to be played from the heart. I think there is a line between serving one’s self and serving the music, and those things should be kept in balance. The ability to play is a gift, given to the player for the purpose of passing it on.

What do you think is the main characteristic of you personality that made you a bluesman?

A knack for improvisation, good timing, and being able to say what I need to say with few words (and notes). I think that a blues player can say a lot with a little bit. Albert King is a great example. Not a lot of licks, but his phrasing and timing were dead on.

I do have to admit that when I write I have to be careful about getting too complicated. Sometimes I think too much.

What turns you on? Happiness is……

Watching the garden grow in my back yard, catching a big fish, a beautiful guitar, being loved.

Is there any similarity between the blues today and the “BLUES OF THE OLD DAYS ”?

I’m lucky to have been around when a lot of the first wave of Chicago blues artists were still there. That first group created the genre, and I think that they set a standard that is not going to be topped. I would say that by and large, the great blues songs have been written and performed, and it’s pretty tough to improve on that. I think that today there are more people than ever recording and playing what is called blues, but there is not a lot of depth to some of it. And rock elements have become a big part of it, as in other forms like country music. It’s just a musician’s nature to pick up sounds that they hear, and blues is no longer isolated in the places it began, like the American South, or in the urban neighborhoods that it was played in after it came North. Corporate radio doesn’t help either. You are much more likely to hear Stevie Ray Vaughn (who I believe was a very good player) than Jimmy Rogers. Not that there has ever been a lot of blues played on mainstream radio.

There are still people carrying on the tradition, though. There are players whose parents were in the first wave, people like Lurrie Bell, Eddie Taylor Jr., and Kenny Smith. I personally play with a number of old friends, and we all came into this music as enthusiasts, stayed around, and are still trying to play it as we knew it and learned it then. I still love it when it all comes together and feels right.

What advice would you give to aspiring musicians thinking of pursuing a career in the craft?

I remember telling my mother what I was going to do, and how she responded, “You can’t do THAT!!” But seriously, there is a lot of music to absorb, and I would do a lot of listening. There are recordings. There are live performances. YouTube is a great resource. More than anything, know that this is what you care about playing. I find it disheartening that some people go into blues because they think it’s the best path to career success. That does nothing for the music. People might also want to be aware that there are a lot more players chasing a lot fewer gigs.

How has the music business changed over the years since you first started in music?

It is kind of sad to play to audiences that are staring at their phones.

When I started, technology was pretty much analog recording, and telephones had cords. We started a band, played in clubs, and hoped to get enough attention that someone would find it worthwhile to record us. And you needed a studio to record on tape. Now there are more and more digital tools and people can record and promote themselves. This is a good thing, and a lot of musicians do a good job. It’s easy to start your own independent label. On the down side, particularly in the pop field, is what seems to me to be a manufactured sameness. But then, I remember being asked to shut the door to my room and turn the volume down on the “noise” that I was listening to.

One thing that is the same for blues is that it is still released on small independent labels. That will most likely remain the case.

Any comments about your experiences with the new generation at Old Town School of Folk Music

I’m really fortunate to have been at the Old Town School for nearly 13 years now. I’ve taught people from 8 to 80 how to play the bass. Some are very into it, some are exploring different experiences. I’ve been teaching one 10 year old boy since last year. He has really taken to it and It’s exciting and moving to play songs with him and watch him learn. I also teach our blues ensembles, which is a lot of fun. Their graduation is to play a 30 minute set at Buddy Guy’s Legends. There is no place like the Old Town School. It’s also a great place to see a show. I catch one there whenever I can.

Lurrie Bell

700 Blues (Delmark) Bassist: Harlan Terson

Instrument:'63 Fender Precision

Bell is a strikingly original blues guitarist, and 30 year vet Terson is a great blues bassist. His pulsing, deep-pocket grooves----and Lurrie's knife-edged guitar work----make this a real feast.

(Gregory Isola)

From Bass Player, September, 1997

Copyright Miller Freeman, Inc. used by permission.